The European energy crisis is one of the biggest “black swans” in 2022.

In its latest annual economic outlook, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) forecasts that the global economy will face weak growth in 2023, with growth slowing from 6.0% in 2021 to 3.2% in 2022 and 2.7% in 2023 . Among them, the impact of the Russia-Ukraine conflict that triggered the European energy crisis was particularly emphasized.

European Commission Economic Commissioner Paolo Gentiloni also said earlier this month that Europe will slip into recession this winter and will not resume growth until next spring.

How did the European energy crisis evolve to this point, and where will it go in 2023?

European Energy Crisis Timeline

In December 2021, as the global energy market rebounded in the global economic recovery, natural gas prices have already hit record highs. A slowdown in Russian gas exports to Western Europe in January sent gas prices up 30%. In February, Japan agreed to divert some of its liquefied natural gas (LNG) imports to Europe, and the Russia-Ukraine conflict erupted after months of tension.

In March, Canada and the United States quickly ordered a ban on oil and gas imports from Russia. Due to its heavy reliance on Russian energy, the EU has taken a more cautious approach, agreeing to cut Russian gas purchases by two-thirds by the end of 2022. In April, the World Bank warned that the energy crisis would trigger the biggest commodity shock in 50 years. In May, European countries began to emerge as major players in the global liquefied LNG market, pushing up cost prices significantly. In June, some steel, chemical and fertilizer makers began shutting factories in Europe due to soaring oil and gas prices and concerns that Russia might cut off energy supplies.

In July, Germany raised its natural gas shortage alert level and announced that it would restart coal power plants. Governments of EU member states have pledged to reduce gas demand by 15% in winter. In the same month, Russia’s largest natural gas pipeline to Europe, “Beixi No. 1”, was shut down for 10 days due to routine maintenance.

In August, the Russian side announced that the “Beixi 1” will stop gas for another 3 days from August 31. In September, Russia announced that the “Beixi 1” would be shut down indefinitely, which disrupted the plans of Germany and other European countries to replenish their energy reserves before winter. At the end of the month, the “Beixi No. 1” and “Beixi No. 2” pipelines ruptured.

That same month, the European Union approved a regulation promising low-cost electricity producers to return profits above revenue caps to their national governments to raise 140 billion euros, which will be used to subsidize consumers. The European Commission also proposed requiring countries to reduce overall electricity demand by at least 10% by the end of March.

In October, OPEC+ members including Russia and Saudi Arabia agreed to cut oil output by 2 million barrels per day despite the ongoing energy crisis, citing “uncertainties surrounding the outlook for the global economy and oil markets”. In November, the European Union met its goal of filling 80% of its natural gas reserves by the 1st of the month. By mid-November, the EU’s gas storage capacity once reached 95.50%. At the same time, the European Commission stipulated in an implementing regulation that EU countries should meet the 90% gas storage target by November 1, 2023.

As of December 26, according to data from the European Gas Infrastructure Organization (GIS), the EU’s gas storage capacity was 83.21%.

LNG, restarting coal plants and renewables

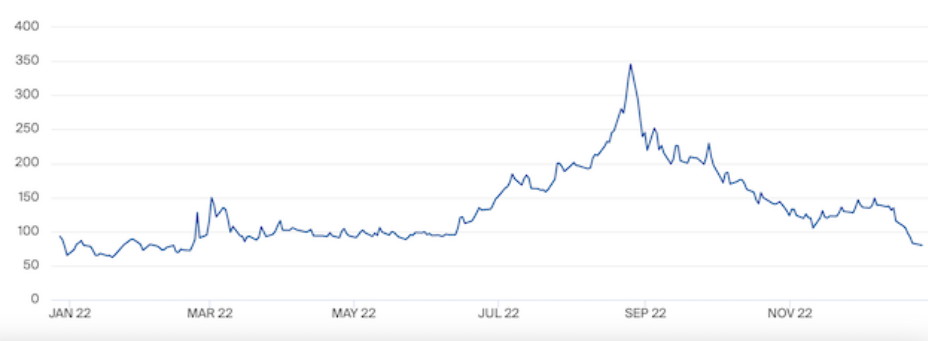

The good news for Europe is that energy prices have come off their peaks over the past three months. European benchmark Dutch TTF natural gas futures have fallen to 80.990 euros per megawatt-hour from a peak of 350 euros in August, according to London-based Intercontinental Exchange (ICE) data. Electricity prices in Europe have more than halved over the same period.

But that hasn’t lessened the uncertainty about the future. EU countries are working on a multi-pronged approach to replace natural gas from Russia in their energy mix.

On the one hand, as part of the REPowerEU programme, EU member states agreed to increase their renewable energy target to 45% by 2030, up from the previous target of 40%. Currently, the EU gets just over 20% of its total energy from renewable sources. A new report from the International Energy Agency suggests that the world could add as much renewable energy in the next five years as it has in the past 20.

On the other hand, countries including Germany, France, Austria, the Netherlands and Italy agreed to bring decommissioned coal plants back into service. In addition, the EU is also negotiating long-term contracts for natural gas with countries such as Qatar.

Prof. Dr. Karen Pittel, director of the Center for Energy, Climate and Resources at the ifo Institute of Economic Research in Germany, told Yicai Global that all feasible means must be considered to replace Russian natural gas. In the short term, she said, the expansion of renewable energy will not be fast enough to overcome the immediate supply gap. So buying limited LNG in bulk is another option.

Ilesh Patel, partner of the British consulting firm Baringa Energy, Public Utilities and Resources, also believes that the domestic supply of natural gas in the European continent is limited. The main oil fields have matured, and production has been decreasing in recent years. The natural gas shortage in the European continent The solution ideas are still external.

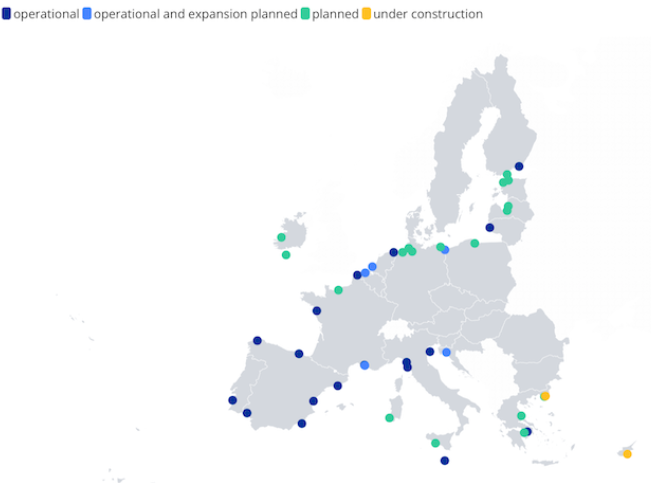

According to data from the European Commission, the EU is already the world’s largest LNG importing economy. In the first half of 2022, the EU imported more than 65 billion cubic meters (bcm) of LNG, worth more than EUR 60 billion. In the first half of 2022, the US is the largest LNG supplier to the EU, accounting for nearly 50% of total imports. Imports of LNG from the United States more than doubled year-on-year.

According to Kpler ship-tracking data, the European Union is on track to set a monthly record for LNG imports in December, when its LNG imports will exceed 19 billion cubic meters in December, beating November’s record of 16.1 billion cubic meters.

Antonio Fatas, a professor of economics at the European School of Business Administration (INSEAD), said in an interview with a reporter from China Business News that although LNG is a solution, it requires good operation of supporting facilities, such as ensuring orders, transport ships and Infrastructure for LNG receiving points.

At present, a large amount of EU government funds is flowing to coastal terminals to build LNG receiving terminals. In addition, to replace 167 billion cubic meters of Russian gas per year, Europe will need 160 new tankers at a total cost of $35.2 billion, according to the Institute of Shipping Economics and Logistics.

But next winter won’t be easy

“Our REPowerEU program will reduce the demand for Russian gas by two-thirds by the end of this year and mobilize investments of up to 300 billion euros,” said European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen. As a result, we are safe this winter.”

Indeed, the current amount of gas in storage in the EU is well above the five-year average. Soaring energy prices have destroyed demand throughout 2022, and European governments and businesses have responded to the energy crisis, providing an important buffer for Europeans heading into winter. Furthermore, the EU gas supply-demand gap is likely to be narrower in 2023 than in 2022 due to measures related to energy efficiency, renewable energy and heat pumps.

However, the latest report from the International Energy Agency, published in December, found that if Russia’s gas shipments drop to zero and other countries’ LNG imports rebound to 2021 levels, the EU’s potential gas deficit could reach 270 in 2023. One hundred million cubic meters.

Fatas said that if Europeans let down their guard and consumed a lot of energy this winter, they could face bigger problems next winter. “Because Russia is no longer selling gas to Europe. Once we use up all the reserves of resources we have accumulated, we will not have gas for next winter,” he said.

Ben Cahill, an energy expert at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), a U.S. think tank, also said that Europe has made great efforts to replace Russia’s energy imports when entering this winter, and it is relatively prepared. But next winter will be tougher, in large part because EU countries need to prepare for a scenario in which they can fully meet their energy needs without Russia. That includes refilling gas storage tanks next summer in the absence of cheap Russian gas. “The biggest challenge is what happens in the next few years,” Cahill said, “because it’s only going to get tougher.”

Pieter also told China Business News that even if the storage target is met, due to infrastructure constraints, natural gas may still be in short supply in extreme cases of very low temperatures. “Even if we manage to get through this winter, the question is, what happens next winter. If we basically use up the stored gas in the next few months, it will be very difficult for us to fill it up again without Russian gas. Fill the tank,” she said.